One: Internationalism—>national liberation—>anti-nationalism?

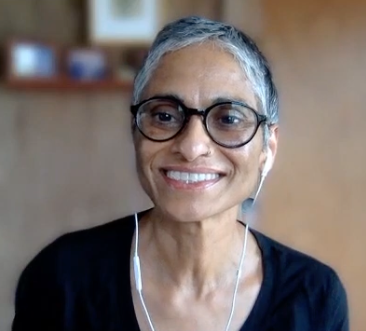

In the nineteenth century, most anti-capitalists were internationalists (and sang The Internationale). In the twentieth century, most were nationalists and called for national liberation. Today, things may be shifting again. National liberation’s record is not good: national sovereignty, where achieved, has not ended capitalist exploitation, the nationalist idea that people have an intrinsic tie to discrete plots of land seems implausible in our era of mass migration; and white nationalism’s rise highlights troubling questions about nationalism as such. Nandita Sharma explores some of these issues in her insightful work, Home Rule: National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants (Duke University Press, 2020). Taking aim at nationalism’s foundational distinction between “native” and “migrant,” she advances a radical vision of politics that points beyond the nation. Michael Busch conducted a thoughtful interview with her, which you can watch here. You can also learn about her book on her publisher’s website, which is here.

Two: mass incarceration without prisons

Most Americans agree that it is time to end mass incarceration but there is a risk that we will reproduce elements of the policy as we try to construct alternatives. If we think of mass incarceration as something that specific actors do through specific institutions—like police and prisons—then we might conclude that the absence of these things is also the absence of mass incarceration, which could be a mistake. Mass incarceration is a social relationship between the state and people, and various actors can enact it and they can do so in diverse institutional contexts. In “Meet SmartLINK, the App Tracking Nearly a Quarter Million Immigrants,” Giulia McDonnell Nieto del Rio shows how a type of digital incarceration operates through phones and apps. No shackles or cells are necessary. You can find her article here.

Three: fighting white supremacy or building an enclave?

Anti-Racist Skinheads Fighting Nazis: The Baldies is an inspiring but frustrating documentary from Twin Cities PBS. It tells the story of The Baldies, a group of Minneapolis-based radical skinheads who stood up to nazi skinheads when they started terrorizing the local punk scene in the 1980s. The Baldies drove them out of the scene by physically fighting them and exposing their noxious views to public scrutiny and they also attempted to build a national network of like-minded anti-fascists. The violence between the two groups mostly took the form of fist fights, but neo-nazis committed occasional murders and, in the documentary, we learn about a Baldie who inadvertently shot a nazi skinhead to death and spent years in prison as a result. The stakes were high, but The Baldies, who were mostly (if not entirely) teenagers, confronted the challenge head-on with a deep sense of social responsibility and idealism. They did this despite ongoing harassment from local authorities, who saw punks as a menace. These things make the documentary inspiring; what is annoying is that it tells the story in a way that minimizes The Baldies’ radicalism. It constructs nazi skinheads as an aberrant subculture, not as an expression of the broader system of white supremacy (which it does not discuss). This suggests, in turn, that The Baldies fought them not as radicals who wanted to transform society but simply because they wanted to rid the punk counter-culture of racism. The documentary devotes a segment to gender dynamics among The Baldies but does not examine their investment in anarchism, which furthers the scene-centered interpretation. Of course, if we understand The Baldies’ as radicals who intended to challenge white supremacy, it makes sense to criticize them for being too counter-cultural and for overemphasizing neo-nazis’ importance. White supremacy is a system that runs throughout society and white supremacist activists are not particularly important to its reproduction. However, setting that aside, I think the evidence indicates that these young people saw fighting white supremacists as a part of a transformative social project, not primarily as a means to resolve problems in their milieu. It is not surprising that PBS would promote liberal fictions—that is basically its job—but it is grating. You can watch the documentary here.

Four: cross-border connections

Non-Spanish speakers who want to follow radical movements and social conflicts in Mexico should consider subscribing to Pie de Página‘s weekly, English-language email newsletter. It typically contains informative, high-quality articles about Mexican politics, particularly land struggles, the feminist movement, and mobilizations on behalf of the “disappeared.” Some of their English-language content (and the type of thing that the newsletter includes) is available here. You can subscribe here. The Taller Ahuehuete newsletter is also a good read. It appears less regularly and tends to focus more on debate than news, but it opens a window onto what anarchist-inspired, anti-capitalist activists in the country are thinking. You can read and subscribe to it here.

Five: space and time in Oakland

Oakland has and has had amazing urbanists. They have helped us situate the city in new historical registers and thus experience its spaces in new ways. For example, in the 1960s, the Black Panther Party located the city in the history of the global battle against colonialism and that changed how many saw its spaces and politics. Andrew Alden, who publishes the Oakland Geology blog, does this in a different way. In article after article, he reads the city’s neighborhoods and iconic sites against the area’s geological past, documenting traces of the latter in the former with text and photos. By showing how the area’s natural and social histories interact, he reveals new dimensions of Oakland’s landscape, You can find his blog here. You can read about his forthcoming book, Deep Oakland, here.

If you’d like to SUBSCRIBE to or UNSUBSCRIBE from this newsletter, please email me at cwmorse@gmail.com and let me know.