One: Fighting digital terror

Upturn is an important voice in tech. Its website says that it advances “equity and justice in the design, governance, and use of technology,” but it is more accurate to say that it challenges the utilization of technologies to subordinate and exploit people of color and working-class people in finance, the criminal justice system, and other terrains. Based in Washington, DC, the nonprofit produces research, supports litigation, and releases an informative weekly newsletter that surveys recent events of pertinence to the intersection of social justice and technology. It breathes fresh air into a tech world dominated by libertarians who think that data and technology are value-free. You can read about their work and subscribe to their newsletter here: http://www.upturn.org/.

Two: Spaces of law-breaking after Roe v Wade

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade, it gave new relevance to old spaces of illegality while drawing our attention to their transformation. I recently read a news article about the opening of an abortion clinic in Tijuana, steps from the Mexican-American border. In addition to describing the clinic, the piece noted criticisms of it made by Crystal Pérez Lira, the founder of Colectiva Bloodys, a local feminist group. Pérez Lira pointed out that the clinic’s prices and location will likely make it inaccessible to locals. Instead of regarding it as a genuine attempt to address reproductive health needs, she indicated that it makes more sense to see it as an extension of Tijuana’s enormous, profit-driven medical tourism industry. The clinic could be a resource for Americans seeking abortions. Tijuana was a crucial node in underground abortion networks before Roe v Wade and American feminist activists routinely directed abortion seekers there. However, Pérez Lira’s comments remind us that class divisions run through these legendary sites of illicit activity and that they operate in a newly globalized context.

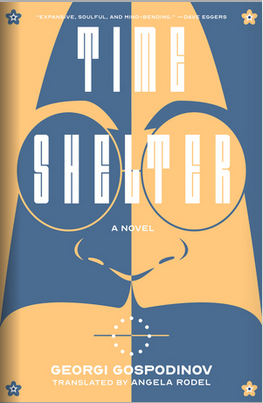

Three: Linking Mexican anarchism and state violence

In Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands (W. W. Norton & Company 2022), abolitionist historian Kelly Lytle Hernández makes a crucial contribution to our understanding of Ricardo Flores Magón and the Magónists, who lay at the center of Mexican anarchism. Her broad survey of the movement unfolds in a truly North American context, organized around a critique of empire and imperialism, which includes an account of the history of the American racial order and policing. This allows her to connect this anti-statist movement to practices of state violence in ways that have been difficult for historians who treat it mainly as a Mexican phenomenon or who fail to acknowledge the importance of racial hierarchies (or both). She discusses her book in this video.

Four: Cities against patriarchy

Societies usually allow some exemptions from prevailing social constraints. These can be deliberate—for example, in border zones, where national sovereignty is ambiguous—and they can be accidental. An instance of the latter existed in the late nineteenth century in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, as April White explains in The Divorce Colony: How Women Revolutionized Marriage and Found Freedom on the American Frontier (Hachette 2022). The state’s lax divorce laws and the city’s accessibility to transportation made it the epicenter of what was known as the “divorce colony,” a place where wealthy white women could unburden themselves of the constraints of marriage after a short period of residency. This geopolitical quirk faded into history, but its legacy highlights a fascinating possibility: could we self-consciously organize entire cities around the goal of undoing patriarchy? If so, what would they be like?

Five: Native American restaurants and anti-colonial eating

The number of Native American restaurants has increased in recent years. In Berkeley, there is Cafe Ohlone, which Louis Trevino and Vincent Medina (both Ohlone) own and operate. In Oakland, there is Wahpepah’s Kitchen. Crystal Wahpepah, the owner and chef, is a member of the Kickapoo Nation, but her restaurant features Native foods from tribes across North America. These restaurants affirm Native survival against settler colonialist violence and also, I think, point toward new culinary opportunities. They necessarily have an anti-colonial referent and, as such, should prompt reflection on the nature of Native American cuisine and on the intersection of food and colonialism generally. This may help us learn how to judge colonialism not just as a political, economic, and cultural force but also as a culinary object. How does it taste? What does anti-colonialism taste like? The rise of questions such as these suggests new forms of culinary and anti-colonial practice.

– – –

If you’d like to SUBSCRIBE to or UNSUBSCRIBE from this newsletter, please email me at cwmorse@gmail.com and let me know.